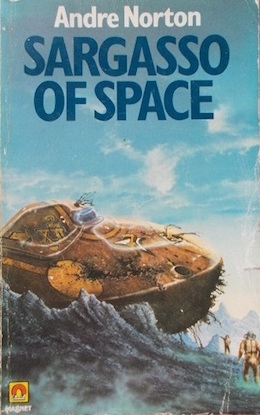

This Andre Norton novel is a complete blank in my memory, except for the title. As far as I can recall, I might even have found it up the library shelf a bit, under its original byline, Andrew North. I wouldn’t have cared if Norton and North were the same person, nor did I know the author was a woman. Library-strafing early-teen me was a complete omnivore when it came to books with rockets on their spines.

By the time I would have discovered it, Sargasso was a few years old: I was a newborn the year it was published, in 1955. I’m sure I enjoyed it, because on the reread—which was effectively a first read—I had a grand time.

Of course it’s of its time, which seems to have become the euphemism of this series. There are racial stereotypes and ethnic terms that are no longer considered acceptable (Negro, Oriental), and the universe is completely devoid of females of any species. It’s all boys and men, except when its creatures so alien there’s no telling if they even have gender.

But that’s the genre. This is boys’ adventure, and it’s Golden Age science fiction. The rockets are shaped like Stubby the Rocket and have fins. The aliens are either weird globular insect-like things or blue lizard men. The good guys are somewhat raffish Free Traders on a beat-up but well-run ship. The bad guys are Hollywood toughs and sleazy con men. There’s a space Patrol and a Survey and Forerunner remnants, blasters and stunners (called sleep rays here) and weapons called boppers, flitters and crawlers and a very basic sort of locator for crewmen in the field.

Protagonist Dane Thorson, nicknamed Viking by the school bully, is a poor kid from nowhere who dreams of the stars. He’s been to Trader school and is now setting out on his hoped-for career as a cargo master. His future is determined by the somewhat unfortunately named Psycho, a computerized Sorting Hat that assigns graduates to their first jobs. Its decisions are final, and there is no appeal.

Psycho dispatches Dane to a somewhat disappointing post: apprentice cargomaster on the Free Trader Solar Queen. In this age of Norton’s universe, the oligarchy is just setting in hard, with rich kids assigned to the wealthy and powerful Companies and kids from nowhere sent to much less lucrative postings.

But Dane is a plucky sort, and the Queen suits him. He fits fairly well into its crew of twelve, though he has doubts and fears and makes mistakes; it’s his first voyage after all, and he has a lot to learn.

The ship quickly finds itself in a predicament. Trade rights to newly discovered worlds are put up for auction, and the Queen pools its limited resources for a year’s exclusive on a world called Limbo. The auction is a gamble: you find out what you bought after you buy it.

It seems at first that the venture will be a bust. Limbo has no apparent intelligent life, and has mostly been burned to the bare rock in one of the Forerunners’ ancient wars. The crew tries to unload the planet for at least enough funds to get off the world where the auction was held, but no one wants it.

Then comes luck, and possible salvation: a mysterious Doctor who claims to be an archaeologist, and who declares that Limbo contains potentially valuable Forerunner remains. He charters the ship, boards with his extensive luggage and his staff of three, and they all jet off to Limbo.

Limbo has indeed been blasted to slag, but parts of it are alive—and more, as Dane discovers. Something plants small oblong fields, and must be tending them at night; during the day, there’s nothing to be seen but the regular rows of plants. Dane sets out to discover what, or who, the farmers may be, and hopefully trade with them.

In the meantime the Doctor and his crew depart for the luridly colored Forerunner ruins, and the Traders begin to explore this planet they’ve bought. They quickly discover that all is not as it seems. One of their crewmen disappears; they begin to find downed spaceships, some quite new and some unimaginably ancient. And one of the Traders, Dane’s fellow apprentice Rip, declares that the doctor can’t be an archaeologist: he’s ignorant of one of the key texts in his field.

Dane, for his part, discovers that the planet has a pulse, a deep resonance that comes and goes. This turns out to be a massive subterranean installation of tremendous antiquity—and the false Doctor and his men have taken control of it.

There’s no sign of the builders, but their geometry and color sense are alien enough to make Dane severely uncomfortable. He surmises that they weren’t human. And, as he and his fellow Traders discover, they built this place as a trap. Hence, the title: a reference to the Sargasso Sea on Terra, where sailing ships used to be trapped and becalmed, and many never managed to escape.

Limbo’s installation has been luring and downing ships for apparent millennia. The Doctor who is now in control is part of a large contingent of interstellar baddies, and they’re using this installation to pull in ships and loot them. The Queen is part of their nefarious plan; once it’s lured it, it can’t lift off without being destroyed like all the rest of the ships that litter the planet.

Dane and his fellows, notably Rip and the inscrutable Japanese steward, Mura, penetrate the alien installation (which is one of Norton’s very most favorite things, a vast underground maze full of incomprehensible machinery), overcome the Doctor and his evil associates, and shut down the machinery that has turned the planet into a death trap. The Patrol arrives in the nick of time and arrests the bad guys; and the Traders work out a deal that leaves the Queen in considerably better financial shape than she was when she landed on Limbo.

In the meantime they discover but don’t do much with the planet’s natives, who are profoundly alien and justifiably hostile. They don’t even have faces, just transparent globes. Norton had a thing for featureless spheres; her nightmares must have been full of them.

This is classic mid-Fifties science fiction, with a touch of Nortonesque subversion. The protagonist is a white person of Nordic extraction, but the crew is fairly diverse. Rip is black, Mura is Japanese—though there’s some residual animus from World War II in that Japan is no more; it was wiped out by an earthquake and a tsunami. Another of the crew, and Dane’s least favorite, is the slickly handsome Ali Kamil—stereotype alert; but he turns out to be just as plucky and loyal as the rest. Norton’s future, as we’ve noted before, is not universally white or American.

What made it really fun for me was playing the movie in my head, with the characters in space boots and bulgy helmets, the weird inhuman inhabitants of Limbo, the proto-Star Trek Rigellians with their blue skin and reptilian traits, and the bare-bones, rattletrap, submarine-like rockets. A dozen years later the world would see the wide corridors and luxurious accommodations of Star Trek’s ships with their artificial gravity, but in 1955, space travel was all about tin cans with hyperdrive.

The tech is deliciously retro. Computers exist, and have decent capability considering, as witness the Psycho, but records are preserved on tape, and astrogators keep actual paper logs of their routes, apparently hand-written. Communications are radio-based, and planetary surveys depend on short-range aircraft—no satellites. Faster-than-light is a thing, and there are ways to communicate across vast distances as well, but when an explorer is on a planet, he doesn’t have much more technological capability than your basic Fifties military pilot.

In 2018, it’s almost impossible to imagine anyone making it into space with tech that basic. How did people survive in ships so poorly shielded that spacers got a tan? And what about the radiation our heroes trek through on the planet, and the toxic mist that leaves everybody coughing and wheezing? There’s no apparent awareness of environmental dangers—just a lot of gee-whiz and gosh-wow and here we are in space! On an alien planet!

But that’s the world of 1955: the heyday of atomic testing, before Silent Spring, when the universe didn’t seem nearly as dangerous—or as fragile–as it turned out to be. The greatest danger then, as Norton saw it, was men, and war was natural and inevitable, if also deplorable. If a man was lucky, he survived. If he was even luckier, like Dane Thorson, he had good friends and crewmates, and he managed in the end to turn a profit, though he had to work for it.

I’m off to Plague Ship next. That one, I’m told, has some issues. We’ll see what I find when I get there.

Judith Tarr’s first novel, The Isle of Glass, appeared in 1985. Her new short novel, Dragons in the Earth, a contemporary fantasy set in Arizona, was published last year by Book View Cafe. In between, she’s written historicals and historical fantasies and epic fantasies and space operas, some of which have been published as ebooks from Book View Café. She has won the Crawford Award, and been a finalist for the World Fantasy Award and the Locus Award. She lives in Arizona with an assortment of cats, a blue-eyed dog, and a herd of Lipizzan horses.

I read Plague Ship recently, but it’s decades since The Sargasso of Space. I think when I first read this I had to google (oops, no, use an encyclopedia!) to find out what the Sargasso Sea was about. It’s so amazing being able to just long press on the word in the title and have a dictionary entry pop up… It’s also very fun to see that Norton’s characters never have access to that level of tech!

I had never read this one before, but enjoyed it very much. After Dane set out his trade wares for the globe beings, I kept expecting him to come back sometime to see what if anything they had chosen or done with his offerings. But, alas, that plot thread was left dangling…

@1 It’s amazing to think how much more tech we have than Norton’s spacemen did.

@2 She dropped threads a lot. I was sorry about that, too. And about the way the aliens never really got to be anything but plot devices. But in a Boy’s Own Adventure, those things were of no interest. It was all about the action and the ray guns.

One of my favorite childhood books (to be clear, it predated my own childhood considerably) was Assignment in Space with Rip Foster (a.k.a. Rip Foster Rides the Gray Planet, originally published in 1952). The story features clean-cut young Rip and some fellow Space Patrol(? I forget the exact organization) members riding an asteroid of pure thorium, at the end of which they just take some anti-radiation pills (and temporarily lose all of their hair) and everything is just fine.

Still a great book, although also most definitely of its time, and less progressive than Norton by a long shot.

@@.-@ Wow. That’s defnitely 1952. People were making road trips to watch nuclear tests–I read a memoir by a woman who grew up on a ranch in northern Arizona, and she talked about how people who lived downwind of the tests started losing kids to cancer. It took years for the clue gun to go off.

The Doctor is the villain?

@6 For sure. He’s not a real archaeologist, and he ends up running the Evil Machine.

As near as I can tell, aside from maybe the one in Voodoo Planet, the Solar Queen’s contracts never worked out the way they were supposed to. I am not at all sure how the ship stayed solvent.

@8, that was supposed to be a Doctor Who joke. Too feeble. But I see ‘the Doctor’ that’s who I think of.

@10: FWIW, I was having the exact same reaction every time I saw “the Doctor”.

@5: There’s actually a free Kindle version of the book up on Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/Rip-Foster-Rides-Gray-Planet-ebook/dp/B004UK07NG/ref=sr_1_2?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1520278792&sr=1-2&keywords=rip+foster

@9 I’m not sure it did. It seems terribly raffish and feckless and charming in a Harry Mudd sort of way.

I would not be surprised if these books influenced Star Trek. They have that flavor to them.

@10 and 11 Headdesk. Duh.

A fair number of Norton works are now Public Domain, available on Gutenberg.

These have been some of my favorite Norton’s.

astrogators keep actual paper logs of their routes, apparently hand-written

And now, I’m thinking of Starman Jones, with an actual astrogation book!

Hmmm- spellcheck doesn’t like ‘astrogation.’ Guess we aren’t living in the future after all!

@5, @11: I remember reading Rip Foster in third grade, IIRC; my homeroom teacher had some kind of point/reward setup for good behavior, and Ride the Grey Planet was my pick. :)

I had hopes from the title that it was part of a larger series; but alas, was not so.

To note, while they’re far more casual about radiation than we were, they weren’t ignoring the issue; everyone on the team had dosimeters, they had limits on the amount of radiation they could take, etc.

Then again, they were using fission bombs to shift the asteroid’s orbit…

@15 — Yeah, and didn’t they also have some kind of magic, radiation-proof bubble wrap they were using to shield themselves?

I also would’ve been happy had there been more books in the series.

“Though there’s some residual animus from World War II in that Japan is no more; it was wiped out by an earthquake and a tsunami.”

Not sure how this proves “animus”. It would put the Japanese in that universe into a very sympathetic position.

…the bare-bones, rattletrap, submarine-like rockets…

Yes, wonderful, that’s just what they were like.

@13 I’ve been either buying hardcopies or paying for ebooks–they tend to be more readable (slightly) when put out by publishers. Though my author-soul kicked hard at this one, with all its OCR weirdnesses. Somebody should have caught those.

@14 There is an actual book stored in a safe. The villains steal one, and our heroes reognize where it comes from by the color of its seal. It’s a big plot point. And I’m like, dude. Star Trek, a dozen years later, had so much more advanced ways of storing information. Huge changes in sf tech over the intervening decade and a bit.

This is one of the things that endears the book to me. It’s so very Fifties.

@17 She blew up Japan. That’s kind of significant, even if Mura was meant to be sympathetic. Kind of, “Karma got them, and now they’ve paid.”

“Submarine-like rockets…”

Who was it, not so long ago, turned actual submarines into spaceships? One (or, iirc, a pair) of the Baen crowd: Flint, Drake, Weber…

Aha! Right on the first try: The Course of Empire by Eric Flint and K.D. Wentworth

Sargasso of Space is one of Norton’s books that always amazed me at how much story she could fit into what was actually a very short book.

Like most of Norton’s protags, Dane always felt like odd man out even though he was accepted by Rip and the rest of the crew. It takes a couple of books for him to feel completely integrated into the crew and he never does feel comfortable with Ali. I think part of Norton’s appeal to young people is that sense of isolation. So many teenagers go through that as they struggle to find their place in the world. Norton’s protags are usually alienated in some way but eventually find acceptance and relationship with others. I think that appeals to young people.

I’m doing some mental comparison to the Liaden books, particularly Balance of Trade. Outsider cargo traders keep coming around in SF.

@22: “Outsider cargo traders keep coming around in SF.”

Particularly in Cherryh!

Richard McEnroe (inexplicably never a Baen author despite having a connection to Jim Baen via the Proteus anthology) had a rather unpleasant variation on the tramp freighter: it’s not _really_ a viable niche, and the big companies have an unassailable advantage. The Shattered Stars has a captain who is seriously burned out having spent his life trying to keep the ship solvent. The Skinner is set decades earlier, when he was young and optimistic and unaware what life was going to do to him….

I loved Van Rycke trading for a better offer. Jellico would have settled for a refund of their auction fees, but the Trader went for the win. Let’s hope Dane is taking good notes.

@james “it’s not _really_ a viable niche, and the big companies have an unassailable advantage.”

I disagree about viability. We still have tramp freighters on Earth, because there are all kinds of places that are just not worth the trouble for the few big companies who have a lock on most of the freight to ship to. Space freight will be no different; and, just as here on Earth, whenever the tramps manage to make a run reliably profitable, then the big companies will come in and force them out. So, it’s never likely that the Solar Queen would make enough profit to parlay into a fleet of interstellar freighters, but it’s highly likely that the Queen and other vessels like her would make enough to keep the ship maintained and to pay its crew–because if they can’t make that much profit, then the places not worth the attention of the large traders will have no trade at all.

@26 Which of course is why the Free Traders exist in the first place. Somebody has to serve the tiny markets.